How do you solve a problem like QAR?

by Simon Ashworth, Director of Policy at AELP

The apprenticeship programme may have weathered the initial Covid-19 storm, but new dark clouds are already gathering on the horizon this week. I can see the headlines now: “Apprentices let down by poorly performing providers”, but we all know it’s a lot more complex than that. However, providers shouldn’t be the only ones worried about the publication of the 2020-21 Qualification Achievement Rates (QAR) and republication of 2019-20 data.

What the data shows us

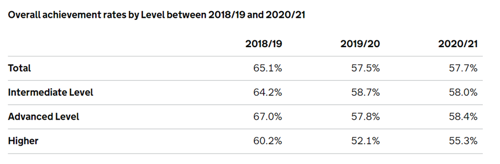

Thursday 31st March 2022 saw the publication of the latest qualification achievement rates (QAR). While it’s not as bad as it could possibly have been, it’s still not a good picture for the apprenticeship programme. Following the data being removed last month due to an error found, the reinstated QAR for FY19-20 is 57.5%. The new published QAR for FY20-21 is 57.7%.

A further breakdown is as follows:

Context

Since the advent of apprenticeship standards and the wider apprenticeship reforms, AELP has questioned the validity of the success rate methodology that sits behind the QAR. We have consistently warned ministers and officials at the Department for Education of the impact that this will have. Make no mistake- the pandemic has landed a blow to the flagship apprenticeship programme’s achievement rates. This in turn threatens to undermine the confidence in the significant financial investment made by the Treasury in apprenticeships – hardly ideal timing, especially with employer groups continuing to lobby for a change to the apprenticeship system and the levy itself.

We must not forget that the success rate methodology was originally designed to work with apprenticeship frameworks. There have been no moves to reflect significant changes in the apprenticeship landscape. The current increase in the cost of living will no doubt result in even more apprentices unfortunately having no choice but to leave their roles to secure higher paid employment in order to make ends meet- when the apprentice minimum wage is set at £4.81 per hour, and the national living wage as much as £9.50, depending on age. We’re now also dealing with an employer-led system, the introduction of more technical and longer apprenticeship standards and the deployment of end point assessment. In a nutshell, the current methodology is simply not fit for purpose.

Why are so many apprentices not completing?

There is common consensus amongst AELP members that a leading cause of apprenticeship non-completion is a result of an apprentice's inability to pass their functional skills exams in English and maths, particularly in level 2 maths. Reformed functional skills qualifications were introduced in the autumn of 2019, but clearly, since then, we have been through a period of unprecedented challenge. The fear is that this remains a hidden issue. Putting aside the well-documented challenges around the pace of changes around remote invigilation, the reformed functional skills have not only become harder- harder than GCSEs, as some providers report- but they still are pitifully funded at just £472 when part of an apprenticeship- a rate which hasn’t changed since 2014. Furthermore, the government has changed the maths and English exit policy on T Levels to make it a ‘condition of funding’ rather than a requirement to achieve the T Level itself. This lack of parity for apprenticeships is simply unfair, which is why AELP has called for equality around maths and English functional skills policy between T Levels, A-Levels, and apprenticeships.

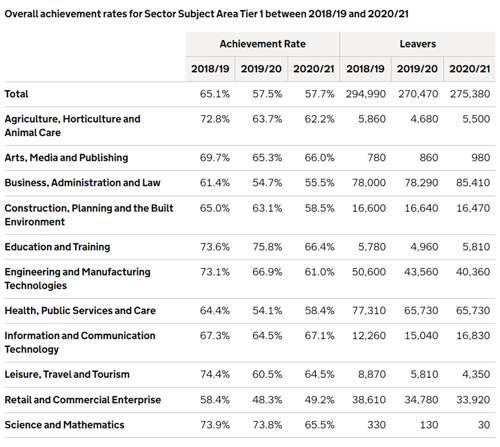

With apprenticeships standards now the only show in town, we continue to gather more intel on the wide range of reasons why apprentices do not complete. Even before the impact of the pandemic hit, to suggest that at least 50% of non-completions are outside of a provider's direct control is an extremely cautious estimate – some providers own analysis suggests it could be nearer 70%. There must also be some nuance around apprenticeships in specific sectors. While the government’s mandatory vaccination policy has now ended, this had a significant impact on withdrawals in adult social care- a sector which already suffers from other factors impacting completion. This highlights the importance of disaggregating the data, which to be fair to the ESFA, is something they recognise more widely in the new apprenticeship accountability framework.

What’s wrong with the methodology?

Unhelpful nuances also remain in the methodology. For example, apprentices who change employers- but continue on their apprenticeship programme- have to be recorded as a withdrawal and a restart, if the gap in employment is greater than 30 days. Where is the logic in that? I would hope that the introduction of the new portable apprenticeships, being piloted from April 2022 will bring this issue to the forefront and it can be addressed once and for all.

Most providers can articulate to Ofsted how significant volumes of non-completers were withdrawn from completing the programme through no fault of the provider, some of the examples include: be it they were offered a higher paid job as the skills they had developed made them more employable, being dismissed from employment or a change of personal circumstances meaning they could not continue either in employment or with their training programme.

The best providers undertake significant analysis of why their apprentices leave and where they go once they have left, and can evidence this well. Through that analysis they can spot trends they can directly influence, such as early withdrawal through ineffective initial skills assessment, or withdrawals later in the programme as the apprentice cannot- despite support- pass their functional skills exams. This process of reflection and continuous improvement is so important, but in isolation, it cannot offset the wider impact of decisions made outside of a provider's direct sphere of influence.

Some positives

Good quality providers will take some heart from the pragmatic words spoken last week at the Annual Apprenticeship Conference, by Ofsted's Chief Inspector, Amanda Spielman. Ofsted recognise the impact of factors outside of a provider's control. While never condoning poor quality, Ofsted's Chief Inspector reassured providers that the Education Inspection Framework (EIF) does not require inspectors to use achievement rates to make a specific judgement. Providers should not be worried that Ofsted will downgrade their provision just because their achievement rates have declined as a result of the pandemic. Even before this announcement, Ofsted has been clear that data will be less important than before when it comes to inspection under the EIF. This is important, because the inspectorate recognises that success rates on frameworks and standards are not directly comparable.

What’s the solution?

Fundamentally, we need a robust system of oversight and accountability which takes the whole system into context. AELP welcomed the commitment by the government in the Skills for Jobs (FE) White Paper back in early 2021 to bring in a new regime that would introduce a “more timely approach to accountability for apprenticeship training providers, based on a wider range of quality indicators.” The introduction of the apprenticeship accountability framework was the perfect opportunity to address the aforementioned deficiencies in the success rate methodology. Disappointingly, the government again failed to grasp the nettle and address the underlying issues. Not only do the success measures need to be updated and reflect the new climate that we’re all working in, the government ultimately needs more trust in the provider community and oversight work undertaken by Ofsted too.

Simon Ashworth is Director of Policy at AELP

How do you solve a problem like QAR?

By Simon Ashworth, Director of Policy at AELP